When you’re a filmmaker / movie nerd, you often get asked “So. What’s your favorite movie?” They either genuinely want to know or want to roll their eyes at your pretentiousness at naming a movie they’ve never heard of. Having seen thousands of films, it’s a very hard question to answer, so I always give my top three: Rear Window (Alfred Hitchcock, 1954), Chungking Express (Wong Kar-Wai, 1994), and Miller’s Crossing (Joel Coen, 1990). One classic, one foreign, one (relatively) contemporary. A good list, I think, but it is still normally met with blank stares. Not that I give a shit. If I thought your taste was better than my taste, it would be my taste.

Those tastes do change as you get older, though, and three films have slowly and steadily moved up my charts due to a combination of repeat viewings and my ever-climbing age (If anyone has figured out a way to slow that down, let me know. I’ll send you an autographed copy of my book or a million dollars or my third born (I’m too attached to my first born, sorry) or something). These films, none of which are new discoveries to me, reveal new things every time I watch them and enrich me as an artist, a film-lover, and a man.

Those three films are Red Beard (Akira Kurosawa, 1965), In the Mood for Love (Wong Kar-Wai, 2000), and Robert Altman’s Nashville (1975).

A week ago, the Criterion Collection (my favorite company in the whole world) finally released a Blu-ray edition of Nashville, what I consider the greatest film on the 1970s, the greatest decade in American film history, a decade that includes Godfather I & II, Taxi Driver, Dog Day Afternoon, Annie Hall, Star Wars, Jaws, Days of Heaven, and dozens of other unbelievable films.

Why I think this movie, made by perhaps the most consistently singular voice in American film history, is better than all of those films, well, that’s a whole essay, a whole book, unto itself.

(HALF-HEARTED SPOILER WARNING: Nashville came out 38 years ago. That is well beyond the ‘spoilers’ period. But, if you haven’t seen this cinematic landmark, you have three choices: 1) Stop reading and go watch it and come back. 2) Read on and hope it makes you want to watch it. 3) Stop reading because you have better things to do. All three options are valid.)

But what I’m going to do, in celebration of at last getting my hands on a restored high-definition version of one of my most treasured films, is talk about what is probably its most famous scene, which also happens to be my favorite scene in movie history:

1. THE TEXT

Nashville is not a musical, but it is about people who make music. As a consequence, there are a lot of songs. Director Robert Altman had his actors write and perform their own songs, with a few exceptions. It’s one of the things that initially kept the film from being embraced by the city that shares its name. These aren’t “real” country songs. They are the actors’ versions of country songs. Some of them are great; some of them are lacking. It doesn’t take away from the film, in my opinion, but it is a choice the film makes that alienates some.

The first way you have to look at this scene (the text) is as a musical scene in a film about music. “I’m Easy” is a good song. Maybe even a great one. Keith Carradine (playing the character of Tom) is a real-life singer, songwriter, and musician. It was the only song from the film to become a hit; it won an Academy Award. Most consider it the musical highlight of the movie, followed distantly by the ridiculously jingoistic “200 Years” that opens the film and the heartbreaking rendition of “It Don’t Worry Me” that ends it.

Carradine’s Tom Frank is a superstar on the verge of leaving his partners and starting a solo career. He’s the Bob Dylan of the film, the John Lennon. The man who not only is a country star, but who could easily be a crossover sensation. The fact that “I’m Easy” is so much better than the rest of the music in the film makes total sense. He is the guy. The other performers are capable and talented entertainers. But Tom is a star. His music should tower above the rest.

So, first but not foremost, this is a scene of a handsome, charismatic, talented singer-songwriter treating us and a club full of people to a new, touching love song. That is the text of the scene. It’s nice. If that was all it was, it would at least work on a pure entertainment level and would still stand out. But that’s not all it is. Not even close.

2. THE SUBTEXT

If you haven’t seen the entire film, this is all you need to know about this scene:

Every woman who gets a close-up thinks Tom is singing about them.

And only one of them is right.

Tom is a member of a Peter, Paul, & Mary-type group called Bill, Mary, & Tom. Mary (Cristina Raines) is married to Bill (Allan Nicholls) but has been having an affair with Tom for who knows how long and is in love with him. It would probably be a stretch, at least in the narrative of the film, to call Tom and Bill “friends” but this is still a gross betrayal on the part of he and Mary. If the affair was to be discovered, it would truly lead to the dissolution of their band, but, with Tom’s solo aspirations, he may be hoping for that to happen.

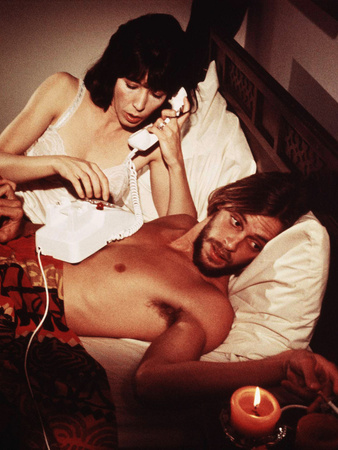

Opal (Geraldine Chaplin) is a reporter for the BBC. Or, at least, she says she is. But at one point she refers to it as the “British Broadcasting Company”, not “Corporation”, revealing her to be a fraud and perhaps a crazy person pretending to be a journalist. She falls into Tom’s bed 48 minutes into the film. It’s not presented as anything more than casual sex, at least to Tom, but Opal is drawn to Tom’s charisma and talent. Who wouldn’t be?

L.A. Joan (Shelley Duvall) is a groupie who is supposed to be in town to visit her dying aunt but is actually doing everything she can to avoid seeing her. She is shallow, careless, self-obsessed. She wears a ridiculous wig and has renamed herself “L.A. Joan”, a swipe at the myth of Los Angeles reinvention. It’s not clear whether or not she has slept with Tom, but she is at his side at the beginning of the scene and at the very least expects to end up in bed with him by the end of the night. Because, well, that’s what groupies do.

Linnea (Lily Tomlin in the performance of her career) is a gospel singer and housewife. She has a decent but inattentive husband and two deaf children. Two months before the film, she had met Tom at a recording studio on his last visit to Nashville. It is unclear whether or not anything happened between them then, but he certainly has not forgotten about her. Earlier in the movie, he calls her home and asks to see her. She intentionally throws up the verbal red flags of “children” and “husband” but Tom is undeterred. She is the only woman in the film that he pursues; the rest all come to him. (More on that in section 3)

As Tom starts singing “I’m Easy”, a song that presents its storyteller as a man turned vulnerable by love, Altman delivers a series of shots that are the culmination of Tom’s philandering that we’ve been watching throughout the first half of the film. Mary, Opal, and Joan all start with the assumption that the song was written for them and that it is being sung to them. Although, of the three, only Mary has any right to think so. But Opal is deluded enough and Joan is self-absorbed enough to be completely wrong. But Mary… Mary thinks she’s special to him. Wants to be. She loves him.

The women watch him in various states of arousal, curiosity, embarrassment, pride.

Except for Linnea. Linnea’s expression, as she sits in the back of the club, as far away from Tom as she can, is blank. It is an unbelievably subtle performance by Tomlin. I’ve watched the scene a hundred times and upon every viewing I convince myself that she’s feeling something different. Is she is sexually aroused to the point of paralysis? Or is she terrified of what she knows she is about to do, which is cheat on her husband? Is she transfixed by the song, allowing the sentiment to get to her? Is she angry? Sad? Hopelessly in love? I don’t know. I worked with Lily Tomlin once, and I wanted to ask her, but decided not to. I’d rather guess.

But as the scene progresses, Tom’s eye line betrays him. Mary is the first to notice that he is isn’t looking at her, and she looks around to see who may be his intended, settling on the plain and quiet woman sitting in the back. She turns away, back to her husband, her face starting to redden. We’re not sure if nutty Opal gets the hint, but L.A. Joan does, following Carradine’s gaze to Lily Tomlin.

At that moment, in that shot, a slow push-in past Duvall and onto Tomlin, the scene becomes about two people staring at each other. This is Tom’s attempt to either seduce Linnea or to express his love for her, depending on how you want to look at it, but she is the “someone kind of special” that the song is for. The look on Tomlin’s face is something I will never shake; it earned her an Academy Award nomination but criminally not a win. Even after the song ends, she holds that look; she can’t even bring herself to applaud.

The scene begins with a mystery and solves it using only images. It is almost an anomaly for an Altman film. He usually allows the viewer to see what they want to see, hear what they want to hear, feel how they want to feel. But this scene is specific in its intent and content and is carefully constructed to deliver them. And its placement in the middle of the much more Altman-esque canvas that comprises the rest of Nashville makes it seem that much more important in contrast.

This is as pure an expression of cinema as you will find.

(WARNING: This last section is about MY thoughts about the scene, what it makes ME feel. I have no way of knowing if any of this was in the filmmakers’ minds, which isn’t the point. Art only means what it means to you.)

3. THE CHADTEXT

In addition to everything I have written above, the “I’m Easy” scene conjures thoughts in me that I’m sure are personal and unique.

To me, this scene is about the fraudulent nature of art.

This is something I think about a lot, so maybe I’m projecting, but this scene reminds me of the scene in Almost Famous where young Cameron Crowe…err…William Miller asks Russell:

“Do you have to be depressed to write a sad song? Do you have to be in love to write a love song? Is a song better when it really happened to you?”

Billy Crudup doesn’t answer the question, but I will:

Nope.

It’s a nice fantasy to think that artists always speak from the heart. That every work they create comes with a piece of their soul planted deep inside. That all songs, movies, and books, are a pure expression of their creators’ thoughts, emotions, and beliefs.

But it’s not true.

Fact is, talent and craft and empathy can easily replicate truth. I know you think you can tell the difference, but you really can’t. Not if it’s done well enough. The Beatles wrote I-don’t-know-how-many love songs and I don’t believe for one second that every one of them was written for a particular person, or even in a state of love. All it really takes is a melody and a sweet sentiment and then it gets turned into something special by the immense talents of Lennon, McCartney, Harrison, and Starr. There are musicians who sing torch songs treat but women like meat when out on tour. Novelists who write about the glory of war who would run to Canada before they’d enlist. Directors who make films about injustice who never look at the homeless people they step over on their way to dinner at Spago’s.

The greatest pop song of all time is the 1969 Jackson 5 record “I Want You Back” (with “God Only Knows” being 1A). It was written by the Motown songwriting collective known as The Corporation, and I can’t testify as to what was in their minds when they put it together, but can anything written by four men really be an expression of pure emotion? Either way, what makes that song great is a vocal performance by an 11 year old boy. That boy brought power and life to that song, especially in the chorus:

Oh baby, give me one more chance (to show you that I love you)

Won’t you please let me back in your heart

Oh darlin’, I was blind to let you go (let you go, baby)

But now since I see you in his arms

I want you back

Written by grown men who I’m sure had experienced heartbreak and longing in their lives, but delivered with feeling by a child who probably had no idea what he was singing about.

But, as we know, that 11 year old was Michael Jackson, a being of immeasurable talent.

Listen to the song. I dare you to not believe him.

I mean, did you know Dr. Seuss didn’t really like kids?

The history of art is full of hypocrites and sons of bitches with so much talent that we’ll never know if they ever meant what they said. And it really doesn’t matter.

Bringing it around to Nashville, Tom Frank (like another one of my favorite fictional Toms, Tom Reagan in Miller’s Crossing) is a son of a bitch. Through the first half of the film we have seen him do nothing but use women, escorting them in and out of his revolving hotel room door. He is fucking his friend’s wife. He sleeps with a woman he doesn’t know and at the very least flirts with another, one who is very close to being a teenager. He is a flat-out womanizer.

Bringing it around to Nashville, Tom Frank (like another one of my favorite fictional Toms, Tom Reagan in Miller’s Crossing) is a son of a bitch. Through the first half of the film we have seen him do nothing but use women, escorting them in and out of his revolving hotel room door. He is fucking his friend’s wife. He sleeps with a woman he doesn’t know and at the very least flirts with another, one who is very close to being a teenager. He is a flat-out womanizer.

But talent, craft, and empathy allow him to write “I’m Easy”, a song about love, vulnerability, and insecurity.

And it might be bullshit.

But what about Linnea? The song is for her, right? Didn’t you say that’s the whole point of the scene?

Well…maybe.

Earlier, I mentioned that it is unclear whether or not Tom had slept with Linnea the first time they met. I lean towards ‘no’. And if that’s the case, then the song could just be a ploy to catch what got away last time. Women don’t say “no” to Tom Frank; did Linnea? Does he realize the only way he’s going to get her into bed is to present himself as something he’s not?

I don’t know. Tom could really love her, or at least think so, but he could just as easily not. For some, it’s obvious. For me, it’s up in the air.

But, after their tryst, after Linnea has taught Tom how to say “I Love You” in sign language, he gets a call from his girlfriend back home. His girlfriend. She gets dressed; searches the sheets for her underwear and kisses him good-bye while he is still on the phone. She is a grown woman who knows what she has done. She had come to the club determined to sleep with him. “I’m Easy” wasn’t even necessary. The song could have been written for this girlfriend back home. Every sexual encounter he has had in the film has been an infidelity. In Linnea’s case, it goes both ways.

Altman tricks us into thinking Tom may really love Linnea. And Tom tricks us, and maybe her, as well, using his talent and craft. But really he’s just a womanizing son of a bitch who wrote a beautiful love song.

That’s what the scene means to me.

And only me, probably. But isn’t that what’s amazing about art? My Nashville is different from your Nashville, even though we’re watching the same movie.

*****

Now. Watch the scene again. I’ll wait.

So that’s my favorite scene in film history. There are no guns, explosions, or tits. Hell, there’s barely any dialogue. It speaks to me on multiple levels and teaches me more about filmmaking than I learned in film school (although we did watch Nashville in film school, so…).

If you’ve never seen Nashville, I can’t recommend it enough. It’s not for everyone, but I only believe that because Robert Altman’s style, the way he made movies, was so singular that no one has ever come close to copying it and watching his films now can seem as alien to modern audiences as it was to those in 1975. He was one of America’s great filmmakers, and certainly its most unique. Unique in his own work, yes, but even more so in the fact that “the Altman Touch”, to steal a phrase usually reserved for a certain magical German director, has never been replicated. He influenced many, but no one “does” Altman. It’s just not doable.

I’m sure I haven’t done this remarkable scene and even more remarkable film justice. It is a true American classic and words are incapable of truly describing cinema. And “I’m Easy”, both the song and the scene, will forever define cinema for me.

And I’ll never forget this face: